|

The First Naning War

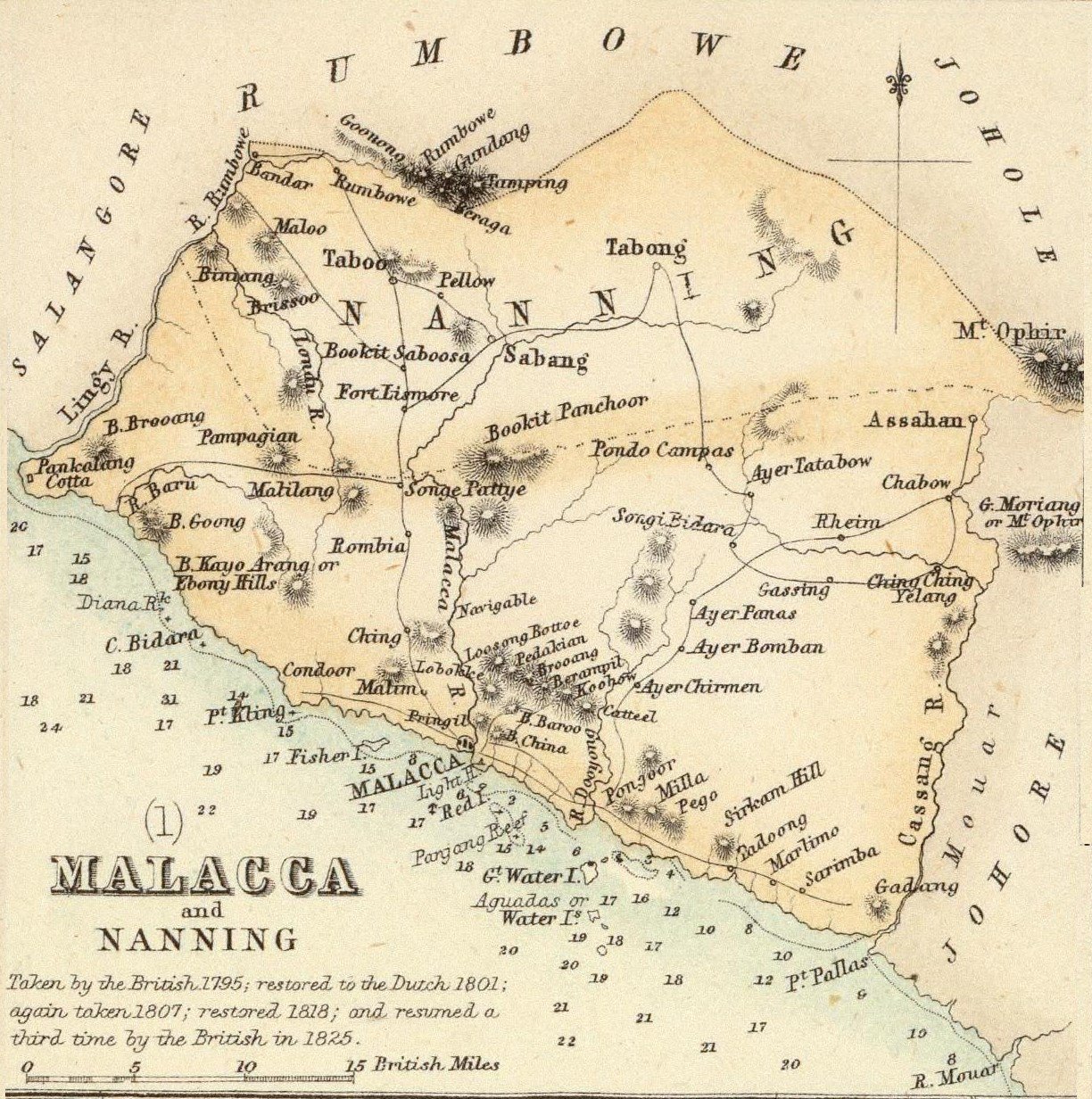

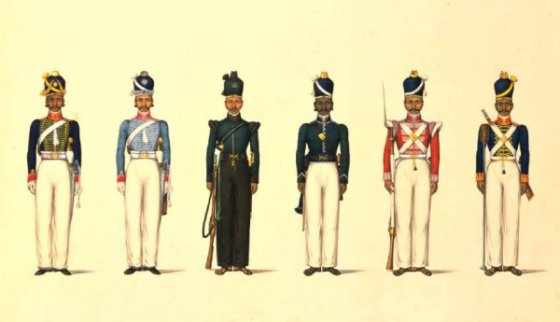

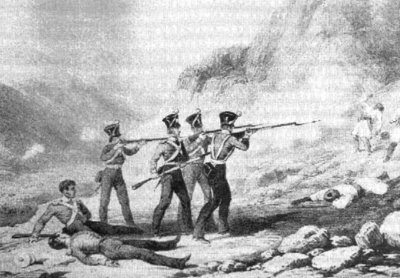

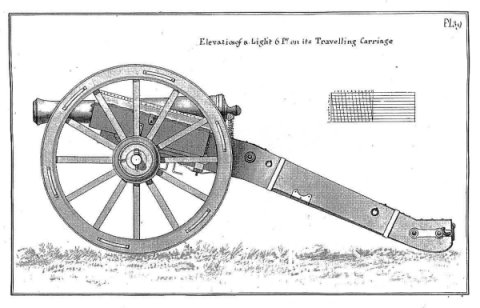

Early in August, 1831, the expedition against the recalcitrant Chief was gathered. It consisted 150 soldiers of the 29th Regiment of the Madras Native Infantry, accompanied by a brigade of two six-pounder cannons of the Madras Foot Artillery and a column of native coolies and convict labour, all commanded by a Captain Wyllie. Dol Said, in the meantime, was also building up his forces, forging an alliance with a number of Naning village and clan ('suku') headmen, as well as seeking the help of the chief of the neighbouring state of Rembau, Syed Sabban. He had managed to convince Syed Sabban that British troops would seek to occupy Rembau as soon as they had conquered Naning, resulting in Syed Sabban joining his resistance with over 500 Rembau warriors. To support the British expedition, a base camp and supply depot was to be set up at the British Government bungalow at Sungai Petai, about thirteen miles march from Melaka. The British intended to send supplies and provisions for the troops by means of boats up the Melaka river, which runs within half a mile of Sungai Petai, and the first boats set off from Melaka on 5th August, 1831. Unfortunately for the British, this plan quickly unravelled when the boats ran aground at Cheng, just halfway to Sungai Petai. The depth of water here was too shallow and the area around Cheng too swampy for the supply boats to proceed farther on their destination in Sungai Petai. The supplies had to be carried overland by coolies from Cheng to Sungai Petai and the boats were forced to return to Melaka on the morning of August 7th. However, as the boats were seen approaching Melaka at 7 PM that evening, rumours rapidly spread to the town that they were war boats sent down the river by Dol Said to capture the town, and the inhabitants of Melaka were soon gripped by an unfounded terror that Melaka was about to be attacked.  The British Expeditionary Force had, in the meantime, left Melaka on August 6th, 1831, arriving at Sungai Petai the next morning. Despite discovering that his supplies had not arrived, Captain Wyllie decided to press on, fearful that any halt in their march might be perceived by the Malays to be a sign of fear and apprehension. The British column arrived at the foot of the hill near Kelemak (across the road from where the Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Dato' Dol Said is today) which marked the boundary between Melaka and Naning. Here, on top of the hill, they encountered Dol Said and some of his men. According to Begbie, "Panglima Dato' who, clothed in scarlet broad cloth, brandished a spear in his left hand, while his right was armed with a sling.". Two Malays fired their muskets at the approaching British column, while the Panglima whirled a large stone at their direction. In an instant, 30 to 40 Malays emerged out of the jungle from behind him. One of the British guns opened fire with grapeshot. The Malays stood their ground but disappeared into the jungle after the third volley. The British column now marched on to Alor Gajah and reached Perigi Datuk (known today as Paya Datuk) on the morning of the 8th of August, 1831. The less than two mile march from Alor Gajah to Paya Datuk had taken the column almost eight hours to accomplish, due to the the difficulty of moving their buffalo-drawn artillery through the narrow jungle path and constant sniping by the Malay muskets from the jungle undergrowth. Their food supplies were also running low, though one day's supply of rice was obtained from a Chinese trader in Alor Gajah. On the next day, the column reached the foot of Bukit Busok, where they found a well-defended Malay stockade at the summit of the hill, with felled trees blocking the path up the hill. As coolies attempted to cut through the felled trees leading up to the stockade, the Malays fired a volley of musket fire at the British column, wounding a sepoy and a coolie. The 6-pounder cannons fired two volleys of grapeshot at the stockade in reply and the Malays appeared to withdraw from the stockade.  Malay 'jinjal' or swivel gun

Not being able to cut through the obstacles in the path up the hill, the British column then moved round the base of the hill, trying to find another path up to the stockade. As they did so, the Malays re-occupied the stockade and fired down upon the British column as it moved round the hill and headed towards the plain of Melekek, where the British column struck camp. For the next few days, the British encampment at Melekek was under constant fire from muskets and jinjals (swivel guns) at stockades the Malays had set up in a number of hills surrounding the Melekek plain. The British column were now in a critical situation. They were completely surrounded, with Malays swarming around in increasing numbers and constantly firing from high ground down upon their exposed position in Melekek. With only 150 armed men, they did not have the manpower to establish defended outposts in their rear, meaning their lines of supply and communications were completely cut. There was still no sign that their supplies had arrived in Sungai Petai and their provisions were by now completely exhausted. On the evening of the 10th of August, the British troops in Melekek heard musket fire in the distance to the south - the British supply convoy at Sungai Petai was under attack by the Malays. Wyllie sent a small party of sepoys and 70 coolies towards Sungai Petai in the hope that they would be able to assist the Sungai Petai encampment and bring back any stores they may have. However, the party was attacked in their march south and had to retreat back to Melekek. Of the 70 coolies, only 17 returned - the others having either been captured or fled into the jungle. Many of the Malay coolies in the British column had put on white flowers in their hair - ostensibly because it was a customary ritual to celebrate a local festival at the time. It was subsequently discovered that the flower was actually a signal to Dol Said's men that they were friendly to their cause and should not be fired upon.  The British troops surrounded at

Melekek now had to face the fact that attacking Dol Said's stronghold

at Taboh was now impossible and Captain Wyllie ordered a retreat back

to Melaka. With most of their coolies gone, the British had to abandon

all their tents, baggage, stores and equipment, only bringing along

their 6-pounder guns. The march south was slow and difficult, the

Malays having felled trees in great numbers and throwing them across

the road to impede their retreat, as well as sniping at the retreating

troops with their muskets and jinjals. As the British column retreated

south, they encountered a hastily-constructed Malay stockade at Kelama,

which poured a heavy fire upon the column. Grapeshot from the British

cannons failed to dislodge the Malays and Wyllie was forced to assault

the stockade. He led a frontal assault on the Malay stockade and while

the Malays were busy engaging this force, another British force moved

round the flank and fired a volley of musket fire from the rear,

forcing the Malays to abandon their position. The British troops surrounded at

Melekek now had to face the fact that attacking Dol Said's stronghold

at Taboh was now impossible and Captain Wyllie ordered a retreat back

to Melaka. With most of their coolies gone, the British had to abandon

all their tents, baggage, stores and equipment, only bringing along

their 6-pounder guns. The march south was slow and difficult, the

Malays having felled trees in great numbers and throwing them across

the road to impede their retreat, as well as sniping at the retreating

troops with their muskets and jinjals. As the British column retreated

south, they encountered a hastily-constructed Malay stockade at Kelama,

which poured a heavy fire upon the column. Grapeshot from the British

cannons failed to dislodge the Malays and Wyllie was forced to assault

the stockade. He led a frontal assault on the Malay stockade and while

the Malays were busy engaging this force, another British force moved

round the flank and fired a volley of musket fire from the rear,

forcing the Malays to abandon their position.The column finally reached Sungai Petai, where they found the 15 men of the supply convoy besieged there. The Malays had by now erected a strong stockade at Rumbia, blocking the British retreat to Melaka and from which they could launch hit-and-run attacks on the Sungai Petai encampment and on any reinforcements from Melaka. Without further reinforcements, Wylie could not proceed any further and could only build a stockade at Sungai Petai to boost his defences against further Malay attacks. On the 12th of August, a small party of Sepoys and coolies bearing supplies was dispatched from Melaka to re-supply the besieged encampment but they were attacked, with the a grenadier killed and another wounded. While the sepoys managed to reach Sungai Petai, the coolies had led, abandoning their loads and the supplies fell into the hands of the Malays. Four days later, on the 16th, more reinforcements were sent from Melaka, with supplies of gunpowder, but they too were attacked in force by the Malays and had to retreat back to Melaka. The Malays always selected the going down of the moon, or its obscuration by clouds (before the eyes of sentries could be fully accustomed to the sudden darkness) as an ideal time for a night-attack. So, in the early hours of August 19th, just as the moon dipped below the forest canopy, the Malays launched a sudden assault on the Sungai Petai stockade. The attacked was repulsed by a well-directed fire of artillery and small arms but the Malays had fixed jinjals on high trees surrounding the encampment and the British could find no defence against them. These swivel guns managed to punch over sixty shot holes on the roof of the bungalow in the British encampment. The Malays also also began using fired arrows, causing numerous fires in the thatched roofs and wooden huts in the encampment.  The Malays continued their bombardment of the British encampment with their jinjals. The Sungai Petai defenders managed to destroy one of these with artillery fire and sent out infantry raids to silence the others. The Melaka government had also opened negotiations with Syed Sabban and had, for the payment of the sum of five hundred dollars, had managed to convince him to withdraw the Rembau men from the conflict and not obstruct the retreat of the remaining troops from the Sungai Petai. On 24th August, a detachment of 40 men of the 29th Regiment of the Madras Native Infantry arrived at the Sungai Petai encampment, with orders to evacuate the remaining troops in Sungai Petai back to Melaka. At 8 PM at night, the British troops filed silently out of the encampment but were spotted and the Malays rushed out of the jungle attacking the column. The Malays swarmed over the encampment, putting its buildings to the torch and opened fire on the rear of the retreating column. The flashes of musketry and booming of jinjals in the darkness of the night were soon accompanied by flashes of lightning and crashes of thunder as a storm erupted during the running night battle.  The victorious Dol Said now had a price on his head. This is a proclamation from the Malacca government dated 9 February 1832, offering a reward of 1,000 dollars for the capture of Dol Said and 200 dollars for the arrest of four of his allies. However, the British knew that, with his significant victory over the, it was unlikely that any Malay would even attempt to capture the heroic figure and the British began preparing a second expedition into the interior of Naning.

About the WebMasterWrite to the Webmaster: sabrizain@malaya.org.uk

|

|---|