|

The Second Naning War

One of the main reasons why Dol Said was so successful in his defence

of Naning against the first British expedition was the alliance he

forged with local Naning chiefs and, in particular, the alliance with

Rembau. Following the failure of the first military expedition, the

British sought to break that alliance between Rembau and Naning. On

January 20th, 1832, the British governor Ibbetson sailed up the Linggi

River estuary in HMS Zephyr to Simpang - the confluence where the

Linggi and Rembau Rivers. There he met with Syed Sabban and other

Rembau chiefs and secured their agreement to support the British in the

attempt to capture Dol Said. In return, the British reassured Rembau

that it did not have territorial ambitions over the surrounding Malay

chiefdoms, renounced whatever claims it might have had over Rembau and

recognized it as an independent sovereign state. Syed Sabban was also

promised the liberty to plunder in the upcoming war in Naning. The

British were now poised to mount a second expedition to capture Dol

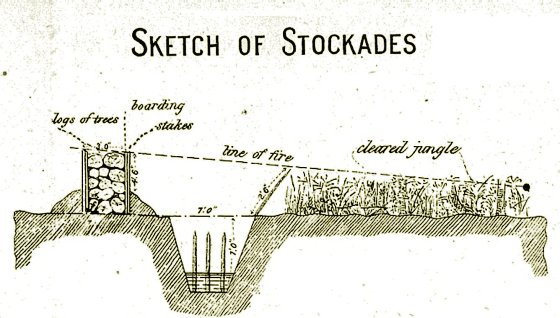

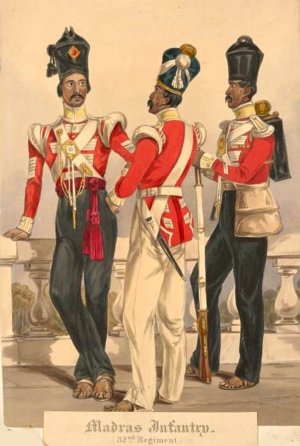

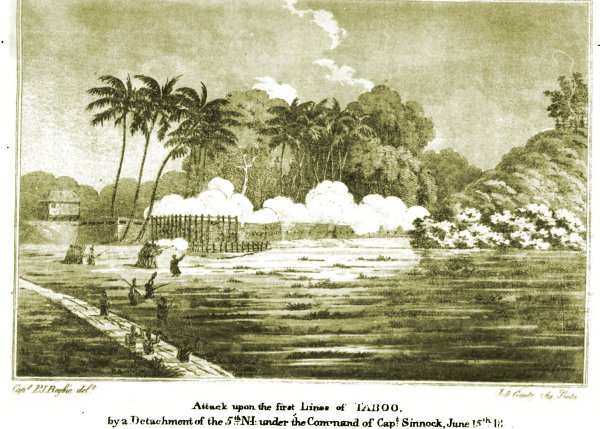

Said and avenge their earlier defeat. HMS Zephyry blockading the Linggi River On 7th January 1832, the advance body of the force marched to Rumbia, where the first Corps headquarters was established. Instead of sending a single force into Naning territory, as they did before, the British strategy now was to send separate detachments of the force in intervals. This was to secure good lines of supply and communications to Melaka, and sufficient forces to ensure a strong response to any rear and flanking operations by the Malays. More time and men were also dedicated to clearing and expanding narrow, jungle-lined roads leading to Naning ahead of the advance body, which was tasked to protecting the engineers, sappers, coolies and convict labour tasked with these road works. By March 17th, the British were ready to launch a full-scale assault on Sungai Petai and attacked a group of five Malay stockades that were constructed on the site of former British encampment there. These were captured, with only one sepoy wounded by a musket ball and eight others wounded by ranjaus. The front of these stockades and the road leading to them had been thickly planted with 'ranjau' - deep pits thickly planted with sharpened wooden stakes and covered over with coconut leaves and tress branches. Most of the British casualties in the war appeared to have been from these ranjaus rather than from musket and jinjal fire or close combat. The stockades themselves were placed in the shape of a crescent, so as to concentrate their fire on the cleared area in front. They were about four feet high, and composed of horizontal piles of wood, the outer and inner rows being about three feet apart and the interstices filled up with earth and logs. Loop-holes for the musketry, and embrasures for the jinjals were cut in them.  wo days later, on March 29th, the British then launched an attack on a very strong Malay stockade west of Kelemak, towards Lendu, on the left flank of the British advance. An advance party of the Malay contingent, led by a Chinese Malay called Soon Kien, was pinned down by heavy fire from the Malay stockades. The main British force then advanced, with sepoys from the 5th Regiment launching a right flank and frontal assault on the stockade and grenadiers from the 29th Regiment under Lieutenant Harding attempting to surprise the Malays on the left flank. The 5th Regiment troops found themselves pinned down by heavy fire as they lay down and crawled forward, musket balls ploughing the ground around them. However, as soon as the 29th Regiment reached the left flank position, they started opening a blistering volley on the stockades and the troops on the other flanks sprung to their feet, firing as they ran towards the Malay defences. The left flank attack had taken the Malays completely by surprise and they fled from the stockades. The last Malay to evacuate the stockade fired a parting shot at Lieutenant Harding, which penetrated his throat and shattered his spine. Harding died of his wounds the next day. Lendu itself was assaulted that day.  On April 12th, the Malays established a stockade at Kelmak,

3/4 mile north of the Sungai Petai encampment, on a hill overlooking

the approach to Alor Gajah. A covering party escorting a detachment of

coolies clearing the road encountered the stockade and, at the first

volley from the stockade, one rifleman was shot through the heart, and

five others wounded. The sepoys immediately fell to the ground, with

the Malays still keeping up a vigorous fire. A section of the party,

led by Ensign Wright, was told to lead a frontal assault on the

stockade, while the other section moved to the right flank of the

stockade. Ensign Wright sprang upon his feet, calling upon his men to

follow him, and dashed forward, not realising that his call had not

been obeyed by any of the sepoys except his orderly boy, the men being

apparently panic struck by their losses. Exposed to the fire of the

stockade, which was all concentrated on him, Wright had hardly reached

a few yards before a musket ball broke his right thigh, and brought him

to the ground. Some Malays rushed out to deliver the final blow but

were driven back by the orderly boy, Emaum Ally who, kneeling behind

his master, fired seven or eight shots over the body. Whilst lying in

this helpless state, Wright received a second ball in the left

shoulder. The eventually rallied and the enemy were driven from their

position, with the help of shelling from a 5 1/2-inch mortar at the

rear. On April 12th, the Malays established a stockade at Kelmak,

3/4 mile north of the Sungai Petai encampment, on a hill overlooking

the approach to Alor Gajah. A covering party escorting a detachment of

coolies clearing the road encountered the stockade and, at the first

volley from the stockade, one rifleman was shot through the heart, and

five others wounded. The sepoys immediately fell to the ground, with

the Malays still keeping up a vigorous fire. A section of the party,

led by Ensign Wright, was told to lead a frontal assault on the

stockade, while the other section moved to the right flank of the

stockade. Ensign Wright sprang upon his feet, calling upon his men to

follow him, and dashed forward, not realising that his call had not

been obeyed by any of the sepoys except his orderly boy, the men being

apparently panic struck by their losses. Exposed to the fire of the

stockade, which was all concentrated on him, Wright had hardly reached

a few yards before a musket ball broke his right thigh, and brought him

to the ground. Some Malays rushed out to deliver the final blow but

were driven back by the orderly boy, Emaum Ally who, kneeling behind

his master, fired seven or eight shots over the body. Whilst lying in

this helpless state, Wright received a second ball in the left

shoulder. The eventually rallied and the enemy were driven from their

position, with the help of shelling from a 5 1/2-inch mortar at the

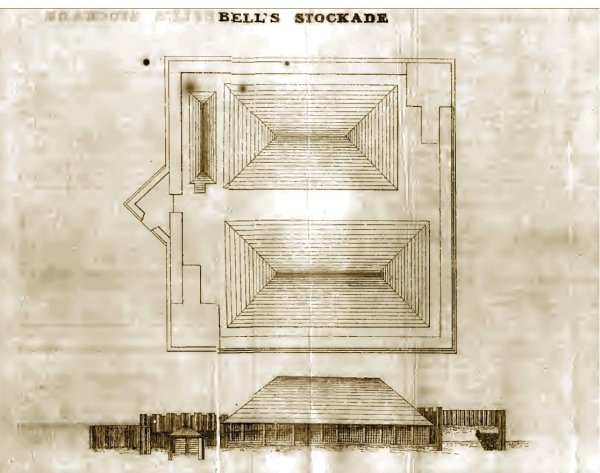

rear. One reason for the success of the British in locating the Malay stockades was their use of guides as spies among the local populace. One such guide, named Billal Munji, was a Naning native of some importance and he would associate with Dol Said's followers at night, and assist in constructing their defences. Information on location and strength of these defences was then delivered to the British by him the next day. By May 3rd, the slow but steady British advance had now reached Paya Datok and their encampment had been moved to Datuk Membangin (in Alor Gajah, where the District and Land Office, pictured here is located today). At 6 A.M., the Malays launched a large attack on the British camp but were driven back when a 12-pounder howitzer was brought to bear on the attackers. The Malays withdrew to a stockade on Bukit Lanjut, a hill overlooking the camp just north of it, and from here they unleashed a lethal plunging fire on the British camp. The British infantry lay down and crawled up the hill as the howitzer then started pounding the Malay stockade. One shot pierced the walls of the stockade, tore out the bowels of one Malay and carried off the leg of another.  The British stockade at their camp in Alor

Gajah, which they called Bell's Stockade.

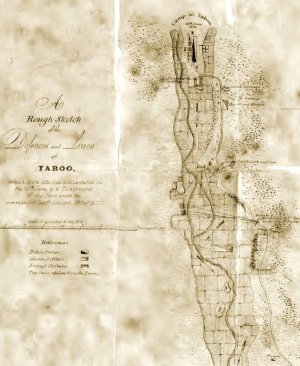

The British infantry then rose up and rushed up the hill, one section launching a frontal assault, while the other, led by an Ensign Walker, moved to the rear of the stockade to block the retreat of the Malays. But the Malays were fully prepared at this stage of the war for flanking movements and as Walker came unexpectedly up and over the earthworks, the Malays unleashed a deadly volley. A musket ball pierced his heart, and he fell dead to the ground. Three sepoys behind him were also wounded by the volley. Fighting did not cease until noon and Walker was buried at the camp that evening. His grave can still be seen today in the compound of the Sekolah Kebangsaan Alor Gajah 1. On May 21st, the Naning spy Billal Munji reported that the Malay stockades at Bukit Busok were very lightly manned that day, due to its troops being in the surrounding countryside foraging for food. Syed Sabban, his Rembau Malays and the Malay Contingent decided to launch an attack. The assault was preceded by an artillery bombardment to distract the enemy as Syed Sabban's men marched up the steep hill path to the stockades. On hearing the beating of Syed Sabban's war drum, the few defenders in the stockades fled and Syed Sabban's men swarmed over the ramparts. They found eight stockades at the summit, seven of which were connected by breast works and formed a crescent, whilst the eighth on a detached eminence flanked the right of the position. There ramparts had several boarded stages, apparently for the purpose ot affording protection from the shells. The troops also found the skeletons, and severed skulls of five of the men, who had been left on the ground. The British decided against occupying the stockade, as their main force was still some distances away in Alor Gajah, and Syed Sabban was ordered to abandon the position and put it to the torch.  On May 27th, Syed Sabban with 40 Rembau men, a detachment

of the Malay Contingent and 12 sepoys of the 46th Regiment were ordered

to attack and occupy the Malay stockades at Bukit Pereling, the final

line of defence left before Dol Said's stronghold at Taboh. Bukit

Pereling was crowned by three stockades in echelon at its summit but

Syed Sabban found it abandoned. At the foot of the hill, he saw a large

breastwork, flanked by a smaller one. Syed Sabban's men rushed downhill

towards it and it was easily captured, the only casualty of the battle

being a Naning Malay who was krissed by Syed Sabban's head warrior,

Panglima Perang Bala Che Lo. Three days later, British units arrived

and established their new headquarters at Pereling. To the sound of

'British Grenadiers', the Union jack was hoisted on the hill and a few

howitzer shells were fired in the direction of Dol Said's stronghold at

Taboh just a few miles away. On May 27th, Syed Sabban with 40 Rembau men, a detachment

of the Malay Contingent and 12 sepoys of the 46th Regiment were ordered

to attack and occupy the Malay stockades at Bukit Pereling, the final

line of defence left before Dol Said's stronghold at Taboh. Bukit

Pereling was crowned by three stockades in echelon at its summit but

Syed Sabban found it abandoned. At the foot of the hill, he saw a large

breastwork, flanked by a smaller one. Syed Sabban's men rushed downhill

towards it and it was easily captured, the only casualty of the battle

being a Naning Malay who was krissed by Syed Sabban's head warrior,

Panglima Perang Bala Che Lo. Three days later, British units arrived

and established their new headquarters at Pereling. To the sound of

'British Grenadiers', the Union jack was hoisted on the hill and a few

howitzer shells were fired in the direction of Dol Said's stronghold at

Taboh just a few miles away. On June 15th at 6.30 A.M. in the morning, after one of the heaviest rainstorms of the year, the British commenced their assault on Taboh. The Malay stockades peppered the advancing British with jinjal shots, as the great drum of Taboh boomed the alarm incessantly (the village is named after the 'taboh', a long, cylindrical drum). The British replied with with howitzer and 12-pounder howitzer shots, which emptied this first line of stockades. The British advanced, coming up to a deep and rapid, but very narrow, stream, Sungai Siput, which was now much swollen by the heavy rains of the morning. The surrounding padi fields were also knee deep in water, and the stream could only be traversed in a few places. While the British were endeavouring to to cross the stream, the British 6-pounders captured by Dol Said opened fire on the British with round shot, the balls falling short by a few yards, and bounding over the detachment, which withdrew to the cover of the captured stockade. More British detachments arrived on the scene from Pereling and they pushed on to the Taboh lines, as well as at two stockades flanking the Malay lines. Felled trees on the road obstructed their advance. They successfully captured the Malay stockade on a steep, conical hill Bukit Penyalang ('Execution Hill') on the left flank of the Taboh lines. The British units now paused and Syed Sabban's Rembau Malays and the Malay Contingent now moved towards the last defences at the Dol Said's fortified house, about six hundred yards further on. Only a small body of men were left there operating the captured British 6-pounders. They fired a round or two on Syed Sabban's advancing party, after which they fled the field. The battle was now over, British casualties being only two sepoys wounded by musketry and and three by ranjaus. It was thought the Malays suffered four wounded by artillery, one of whom was a son of Dol Syed, whose arm was said to have been broken by two fragments of a shell. On the next day, the Union Jack was hoisted at Dol Said's house. The two-year Naning War was essentially over.  Dol Said fled Naning and sought refuge in Seri Menanti. The British issued a reward of 2000 dollars for his capture, with little success, but he eventually surrendered to the British on 4 February 1834, in return for the promise of a pardon. After his surrender, Dol Said was permitted by the British to remain in Melaka, his presence and good treatment being regarded by the British as a means of securing the goodwill of the local population as well as the neighbouring Malay chiefdoms. The British provided him with a house and some land in Melaka, as well as a pension of 200 rupees a month. While in Melaka, Dol Said practised as a traditional medicine man and remained well-respected by the Malay population. Dol Said remained in Melaka until his death in August 1849, after which he was buried in his home village of Taboh. he Naning War marked one of the earliest attempts by the British to safeguard their interests in the Malay Peninsula through direct military intervention. However, the humiliating defeat they suffered initially, the surprisingly determined resistance from the Malays and high costs incurred in mounting the expeditions resulted in the British adopting a less aggressive, non-military policy towards dealing with the rest of the Malay states for the next few decades. Instead, the British sought to expand their influence economically and politically among the Malay rulers, culminating in the creation of the residential system 40 years in 1874. In the intervening years, however, the difficult experience of the Naning War certainly made the British leave the Malay States on the peninsula pretty much alone.

About the WebMasterWrite to the Webmaster: sabrizain@malaya.org.uk

|

|---|