|

|

Perak's 'little war

Isabella Bird was one of the indefatigable spirits of the Victorian

era,

travelling the world from the Rockies to Korea, Nova Scotia to Morocco.

Her

book 'The Golden Chersonese' finds her departing from Japanese shores

and

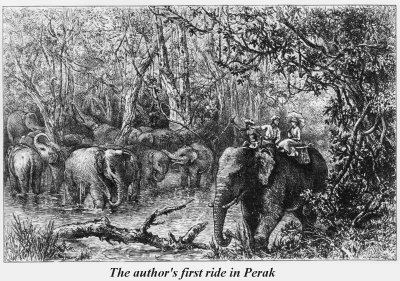

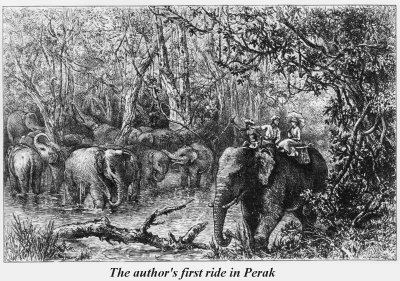

travelling the length of the Malay Peninsula - sometimes on the back of

an

elephant. The extract below, written in 1879, chronicles her

impressions

of the 'little war' in Perak.

It is singular that the fall of Perak as an independent State was

brought

about by what may be called a civil war among the Chinese, who in 1871

were

estimated at thirty thousand, and were principally engaged in

tin-mining

in Larut. These Chinamen were divided into two sections--the Go Kwans

and

the Si Kwans; and a few months after Sultan Ismail was elected, a

dispute

arose between the factions. Both parties flew to arms, and were aided

with

guns, ammunition, military stores, and food from Pinang, Pinang Chinese

having

previously supplied the capital needed for working the mines. The

settlement

was kept in perpetual hot water, its trade languished, and in return

for

military equipments the Chinese of Larut sent over two thousand wounded

and

starving men. The Mentri, the Malay "Governor" of Larut, although aided

by

Captain Speedy and a force of well-drilled troops recruited by him in

India,

and possessing four Krupp guns, was powerless to restore order, and

Larut

was destroyed, being absolutely turned into a wilderness, in which all

but

three houses had been burned, and, while the Malays had fled, the

surviving

Si Kwans were living behind stockades, while those of the faction

opposed

to that with which the Mentri and his Commander-in-Chief, Captain

Speedy,

had allied themselves, were living on the products of orchards from

which

their owners had been driven, and on booty, won by a wholesale system

of

piracy and murder, practiced not only on the Perak waters but on the

high

seas.

The war waged between the two parties threatened to become a war of

extermination;

horrible atrocities were perpetrated on both sides; and it is said and

believed

that as many as three thousand belligerents were slain on one day early

in

the disturbances. If the course of prohibiting the export of munitions

of

war had been persevered the strife would have died a natural death; but

the

Mentri made representations which induced the authorities of the

Straits

to accord a certain degree of support to himself and the Si Kwans, by

limiting

the prohibition to his enemies the Go Kwans. Things at last became so

intolerable

in Larut, and as a consequence in Pinang, that the Governor of the

Straits

Settlements, Sir A. Clarke, thought it was time to interfere. During

these

disturbances in Larut, Lower Perak and the Malays generally were living

peaceably

under Ismail, their elected Sultan. Abdullah, who was regarded as his

rival,

was a fugitive, with neither followers, money, nor credit. He had,

however,

friends in Singapore, to one of whom, Kim Cheng, a well-known Chinaman,

he

had promised a lucrative appointment if he would prevail on the Straits

authorities

to recognize him as Sultan. Lord Kimberley had previously instructed

the

Governor to consider the expediency of introducing the "Residential

system"

into "any of the Malay States," and the occasion soon presented itself.

An English merchant in Singapore and Kim Cheng drafted a

letter

to the Governor, which Abdullah signed, in which this chief expressed

his

desire to place Perak under British protection,* and "to have a man of

sufficient

abilities to show him a good system of government." Sir A. Clarke, thus

appealed

to, went to Pulo Pangkor, off the Perak coast, summoned the Chinese

head

men and the Malay chiefs to meet him there, and so effectively

reconciled

the former, who were bound over to keep the peace, that they were not

again

heard of. The Governor stated to the Malay chief and Abdullah that it

was

the duty of England to take care that the proper person in the line of

succession

was chosen for the throne. He inquired if there were any objection to

Abdullah,

and on none being made, the chiefs signed a paper dictated by Sir A.

Clarke,

since known as the "Pangkor Treaty." Its articles deposed Ismail,

created

Abdullah Sultan, ceded two tracts of territory to England, and provided

that

the new ruler should receive an English Resident and Assistant

Resident,

whose salaries and expenses should be the first charge on the revenue

of

the country, whose counsel must be asked and "acted upon" on all

questions

other than those of religion and custom, and under whose advice the

collection

and control of all revenues and the general administration should be

regulated.

After the signing of this treaty piracy ceased in the Perak waters, and

Larut

was repeopled and became settled and prosperous.

[*Abdullah informs "our friend" Sir W. Jervois, that his position and

that

of Perak are "in a most deplorable state," that there are two Sultans

between

whom no arrangement can be made, that the revenues are badly raised,

and

the laws are not executed with justice. "For these reasons," he says,

"we

see that Perak is in very great distress, and, in our opinion, the

affairs

of Perak cannot be settled except with strong, active assurance from

our

friend the representative of Queen Victoria, the greatest and most

noble....We

earnestly beg our friend to give complete assistance to Perak, and

govern

it, in order that this country may obtain safety and happiness, and

that

proper revenues may be raised, and the laws administered with justice,

and

all the inhabitants of the country may live in comfort."]

So far, as regards the Sultanate, I have followed the account given by

Sir

Benson Maxwell. Mr. Swettenham, however, writes that Abdullah failed to

obtain

complete recognition of himself as Sultan, and instead of fulfilling

the

duties of his position, devoted himself to opium- smoking,

cock-fighting,

and other vices, estranging, by his overbearing manner and pride of

position,

those who only needed forbearance to make them his supporters. It may

be

remarked that Abdullah was not as yielding as had been expected to his

English

advisers.

The Pangkor Treaty was signed in January, 1874. On November 2d, 1875,

Mr.

Birch, the British Resident, who had arrived the evening before at the

village

of Passir Salah to post up orders and proclamations announcing that the

whole

kingdom of Perak was henceforth to be governed by English officers, was

murdered

as he was preparing for the bath.

On this provocation we entered upon a "little war," Perak became known

in

England, and the London press began to ask how it was that colonial

officers

were suffered to make conquests and increase Imperial responsibilities

without

the sanction of Parliament. Lord Carnarvon telegraphed to Singapore

that

he could not sanction the use of troops "for annexation or any other

large

political aims," supplementing his telegram by a despatch stating that

the

residential system had been only sanctioned provisionally, as an

experiment,

and declaring that the Government would not keep troops in a country

"continuing

to possess an independent jurisdiction, for the purpose of enforcing

measures

which the natives did not cheerfully accept."

As the sequel to the war and Mr. Birch's murder, Ismail, who had

retained

authority over a part of Perak, was banished to Johore; Abdullah, the

Sultan,

and the Mentri of Larut, who was designated as an "intriguing

character,"

were exiled to the Seychelles, and the Rajah Muda Yusuf, a prince who,

by

all accounts, was regarded as exceedingly obnoxious, was elevated to

the

regency, Perak at the same time passing virtually under our rule.

A great mist of passion and prejudice envelops our dealings with the

chiefs

and people of this State, both before and after the war. Sir Benson

Maxwell

in "Our Malay Conquests," presents a formidable arraignment against the

Colonial

authorities, and Major M'Nair, in his book on Perak, justifies all

their

proceedings. If I may venture to give an opinion upon so controverted a

subject,

it is, that all Colonial authorities in their dealings with native

races,

all Residents and their subordinates, and all transactions between

ourselves

and the weak peoples of the Far East, would be better for having

something

of "the fierce light which beats upon a throne" turned upon them. The

good

have nothing to fear, the bad would be revealed in their badness, and

hasty

counsels and ambitious designs would be held in check. Public opinion

never

reaches these equatorial jungles; we are grossly ignorant of their

inhabitants

and their rights, of the manner in which our interference originated,

and

how it has been exercised; and unless some fresh disturbance and

another

"little war" should concentrate our attention for a moment on these

distant

States, we are likely to remain so, to their great detriment, and not a

little,

in one respect of the case at least, to our own.

Write to the WebMaster: sabrizain@malaya.org.uk

The

Sejarah Melayu

website is

maintained solely by myself and does not receive any funding

support from any governmental, academic, corporate or other

organizations. If you have found the Sejarah Melayu website useful, any

financial contribution you can make, no matter how small, will be

deeply appreciated and assist greatly in the continued maintenance of

this site.

|

|