|

|

The Lukut Massacres

It is thought that the civil war that erupted in Selangor

after the death

of Sultan Muhammad may well have been avoided had there not been a

dispute

in the succession. According to the Victorian traveller Isabella Bird,

it

was recognized that Sultan Muhammad had no legitimate offspring, "but

it

was likely that at his death, his near relation, Tunku Bongsu, a Rajah

universally-liked

and respected by his countrymen would have been elected to succeed

him."

Unfortunately for Selangor, the fate of 'Tunku Bongsu', more widely

known

as Raja Busu, was to prove as tragic as that of his State. It is thought that the civil war that erupted in Selangor

after the death

of Sultan Muhammad may well have been avoided had there not been a

dispute

in the succession. According to the Victorian traveller Isabella Bird,

it

was recognized that Sultan Muhammad had no legitimate offspring, "but

it

was likely that at his death, his near relation, Tunku Bongsu, a Rajah

universally-liked

and respected by his countrymen would have been elected to succeed

him."

Unfortunately for Selangor, the fate of 'Tunku Bongsu', more widely

known

as Raja Busu, was to prove as tragic as that of his State.

Raja Busu was a son of Sultan Muhammad who, in 1824,came to Lukut with

his

followers from Selangor, Kedah and other States to develop its rich tin

resources.

He encouraged Chinese miners, especially from Melaka, to settle in the

area

and work the tin mines. He was an effective administrator and Lukut

prospered,

with more and more Chinese miners arriving and expanding the output of

the

mines.

In 1834, Raja Busu decided to impose a ten per cent levy on

all

tin extracted and exported from Lukut. This greatly angered the local

Chinese

miners, as well as their financial backers in Melaka. One dark, rainy

night

in September, 1834, this anger erupted into rage when some 300-400

Chinese

converged upon Raja Busu's palace and surrounded it, angrily shouting

and

demanding that he either come out or they would set fire to his home.

Raja

Busu defiantly shouted back "Muslims are not afraid to die - do what

you

like!"

Upon hearing this, the mob attacked

the Palace and the houses of Malays nearby,

with hundreds being robbed and killed. Not a single soul in the palace

survived.

In the words of Isabella Bird, "these miners rose upon their

employers,

burned their houses, and massacred them indiscriminately, including

this

enlightened Rajah; and his wife and children, in attempting to escape,

were

thrown into the flames of their house. The plunder obtained by the

Chinese,

exclusive of the jewels and gold ornaments of the women, was estimated

at

3,500 pounds. This very atrocious business was believed to have been

aided

and abetted, if not absolutely concocted, by Chinese merchants living

under

the shelter of the British flag at Malacca." Upon hearing this, the mob attacked

the Palace and the houses of Malays nearby,

with hundreds being robbed and killed. Not a single soul in the palace

survived.

In the words of Isabella Bird, "these miners rose upon their

employers,

burned their houses, and massacred them indiscriminately, including

this

enlightened Rajah; and his wife and children, in attempting to escape,

were

thrown into the flames of their house. The plunder obtained by the

Chinese,

exclusive of the jewels and gold ornaments of the women, was estimated

at

3,500 pounds. This very atrocious business was believed to have been

aided

and abetted, if not absolutely concocted, by Chinese merchants living

under

the shelter of the British flag at Malacca."

As survivors fled into the countryside and news of the atrocity spread,

Malays

in the region converged upon Lukut. The Chinese attempted to escape

over

the border to British Melaka - but they were ambushed and killed.

Villages and mines

in Lukut were deserted for years.

In 1846, a Bugis prince from Riau, Raja Jumaat, was

officially appointed by the Sultan

to rule Lukut on his behalf. While Raja Jumaat made great efforts in

trying

to win the support of locals and miners, he was also mindful of the

district's

bloody history and firmly stamped his authority. There was no clearer

reminder

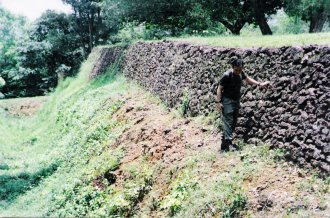

of this authority than the construction of a fort in 1847 that, today,

remains

as one of the most well-preserved Bugis forts in existence. In 1846, a Bugis prince from Riau, Raja Jumaat, was

officially appointed by the Sultan

to rule Lukut on his behalf. While Raja Jumaat made great efforts in

trying

to win the support of locals and miners, he was also mindful of the

district's

bloody history and firmly stamped his authority. There was no clearer

reminder

of this authority than the construction of a fort in 1847 that, today,

remains

as one of the most well-preserved Bugis forts in existence.

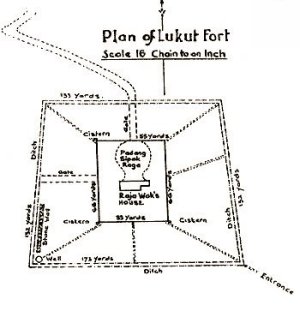

The fort is located on the summit of a hill known as Bukit

Gajah Mati (Hill

of the Dead Elephant) or Bukit Raja, and was accessible by a winding

road

from the foot of the hill. The fort overlooks Lukut town and gave an

unhindered

view of the Lukut river, its surroundings and even the Straits of

Melaka. The fort is located on the summit of a hill known as Bukit

Gajah Mati (Hill

of the Dead Elephant) or Bukit Raja, and was accessible by a winding

road

from the foot of the hill. The fort overlooks Lukut town and gave an

unhindered

view of the Lukut river, its surroundings and even the Straits of

Melaka.

Built by convict labour, it was square in shape and measured

about

200 metres by 170 metres.

Its red laterite stone walls were surrounded by a moat eight

metres

wide and between eight to ten metres deep. A forest of bamboo stakes

were

planted at the bottom of the moat and the barricaded stone walls were

ringed

with the latest Dutch-made cannons. Cannon were also placed at the main

entrance

to the fort, on the north wall, and a smaller entrance on the west

wall.

The fort was further enlarged and fortified during the reign

of

Raja Bot, Raja Jumaat's son, and the Malay garrison stationed there was

strengthened

with the employment of 30 Arab mercenaries. A 'sepak raga' court within

the

fort provided the garrison with sporting entertainment.

The British Resident of Melaka, Captain MacPherson,

reported that the troops

in Kota Lukut wore uniforms similar to those found in Melaka and that

their

conduct was "very orderly and disciplined" The British Resident of Melaka, Captain MacPherson,

reported that the troops

in Kota Lukut wore uniforms similar to those found in Melaka and that

their

conduct was "very orderly and disciplined"

A palace was built in the middle of the Fort for Raja Wok, the

daughter

of Raja Jumaat. Water pools were located at each corner of the fort's

perimeter,

which were replenished with water brought from the river up to the fort

by

bullock cart.

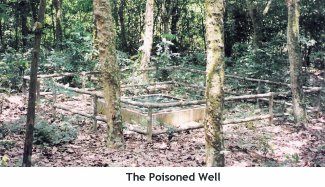

However, the royal household had exclusive use

of a walled well, called the

Princess' Well, which was under guard at all times. Another well

located

outside the fort was called the Perigi Beracun or Poisoned Well, and

was

used for the execution of criminals, who were lowered down the shaft

into

a deadly mix of water, latex and poisonous tree saps. However, the royal household had exclusive use

of a walled well, called the

Princess' Well, which was under guard at all times. Another well

located

outside the fort was called the Perigi Beracun or Poisoned Well, and

was

used for the execution of criminals, who were lowered down the shaft

into

a deadly mix of water, latex and poisonous tree saps.

Raja Jumaat's reign was one of peace and growing

prosperity and ended with

his death in 1864. During Raja Bot's reign, however, Raja Sulaiman of

Sungai

Raya attempted to overrun Lukut, resulting in the fort being used as a

refuge

for women and children fleeing hostilities. Raja Jumaat's reign was one of peace and growing

prosperity and ended with

his death in 1864. During Raja Bot's reign, however, Raja Sulaiman of

Sungai

Raya attempted to overrun Lukut, resulting in the fort being used as a

refuge

for women and children fleeing hostilities.

A battle ensued at Kampong Cina and Raja Bot's forces had to

withdraw

to the fort when every one his Arab mercenaries fled the field after

one of their number

was killed in the fighting. However, the fort's Malay defenders

forcefully threw

back Raja Sulaiman's assault and he was forced to flee back to Sungai

Raya.

Further unrest bewteen Malays and Chinese in later years,

as well as dwindling

tin production, led to Lukut's slow decline. By the time Lukut fell

under

the control of Sungai Ujong in 1878, it was in financial ruin and the

fort

was abandoned. Further unrest bewteen Malays and Chinese in later years,

as well as dwindling

tin production, led to Lukut's slow decline. By the time Lukut fell

under

the control of Sungai Ujong in 1878, it was in financial ruin and the

fort

was abandoned.

Sources:

- “Kota-Kota Melayu”, Abdul Halim Nasir, 1990, Dewan

Bahasa dan Pustaka

- “Sejarah Selangor”, Haji Buyong Adil, 1981, Dewan

Bahasa dan Pustaka

- "A History of Selangor" J M Gullick, 1998, Malaysian

Branch

of the Royal Asiatic Society Monograph No. 28

- "The Golden Chersonese" Isabella Bird, 1883, John

Murray

Write to the author: sabrizain@malaya.org.uk

The

Sejarah Melayu

website is

maintained solely by myself and does not receive any funding

support from any governmental, academic, corporate or other

organizations. If you have found the Sejarah Melayu website useful, any

financial contribution you can make, no matter how small, will be

deeply appreciated and assist greatly in the continued maintenance of

this site.

|

|