|

|

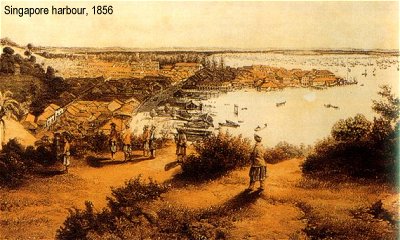

Singapore

From den of pirates to port city

Stamford

Raffles was the son of a sea-captain and had been born on his father's

ship off Jamaica in 1781. His family was poor, and after very little

schooling he became a clerk in the East India Company's office in

London at the age of fourteen. There he worked so hard that he won the

esteem of his employers and at the same time managed to continue his

education during his leisure hours. His chance came in 1805, when

Penang was made a Presidency and he was appointed Assistant Secretary

to the Government there. On the long voyage to the East Raffles set

himself to learn all he could of the language and history of the Malay

people among whom he was to work. Soon after his arrival at Penang this

knowledge led to his being employed as the official Malay translator,

and in 1807 he was promoted to the post of Secretary to the Government. Stamford

Raffles was the son of a sea-captain and had been born on his father's

ship off Jamaica in 1781. His family was poor, and after very little

schooling he became a clerk in the East India Company's office in

London at the age of fourteen. There he worked so hard that he won the

esteem of his employers and at the same time managed to continue his

education during his leisure hours. His chance came in 1805, when

Penang was made a Presidency and he was appointed Assistant Secretary

to the Government there. On the long voyage to the East Raffles set

himself to learn all he could of the language and history of the Malay

people among whom he was to work. Soon after his arrival at Penang this

knowledge led to his being employed as the official Malay translator,

and in 1807 he was promoted to the post of Secretary to the Government.

By

this time, the Napoleonic Wars were in full swing and the Dutch in Java

began collaborating with their French allies in Mauritius in denying

Britain naval supremacy and trade in the East. Britain was compelled to

capture both islands. Mauritius was captured in 1810 and a great

invasion task force came to Penang the next year. From Penang, it moved

down to Melaka where Raffles had been organising an intelligence unit;

and then it crossed to Java, which was quickly captured. By

this time, the Napoleonic Wars were in full swing and the Dutch in Java

began collaborating with their French allies in Mauritius in denying

Britain naval supremacy and trade in the East. Britain was compelled to

capture both islands. Mauritius was captured in 1810 and a great

invasion task force came to Penang the next year. From Penang, it moved

down to Melaka where Raffles had been organising an intelligence unit;

and then it crossed to Java, which was quickly captured.

When the war ended in Europe, the British wanted a powerful

Holland in Europe to act as a buffer between it and France, and so Java

was restored to it. Raffles, however, loathed the Dutch administration

in the East and firmly believed it was in Britain's greatest to retain

Holland's eastern possessions. He was furious but could do nothing.

However, he was saved by his enemies, the Dutch. On their return to

Java, they re-imposed, with greater effectiveness than before, their

old regulations and trade restrictions.

In

late 1818, he was instructed by the authorities in India to see if he

could establish a British trading post at Riau, if this could be done

without a quarrel with the Dutch. He sailed to Penang and then on down

the Straits of Melaka. He took with him William Farquhar, who had been

in charge of Melaka during the war. He did not go to Riau, for the

Dutch had returned there and garrisoned it. He went instead to the

Carimon Islands nearby. Here, he found fresh water, but the harbour was

unsatisfactory. So he sailed from there to Singapore in January 1819,

landing at the mouth of the Singapore River on a beach littered with

skulls - it was then a den of Malay pirates. In

late 1818, he was instructed by the authorities in India to see if he

could establish a British trading post at Riau, if this could be done

without a quarrel with the Dutch. He sailed to Penang and then on down

the Straits of Melaka. He took with him William Farquhar, who had been

in charge of Melaka during the war. He did not go to Riau, for the

Dutch had returned there and garrisoned it. He went instead to the

Carimon Islands nearby. Here, he found fresh water, but the harbour was

unsatisfactory. So he sailed from there to Singapore in January 1819,

landing at the mouth of the Singapore River on a beach littered with

skulls - it was then a den of Malay pirates.

Raffles found a small village inhabited by about 150 Malays

and Orang Laut, who lived by fishing and piracy under the leadership of

the Temenggong of Johore, the actual ruler of that state, since the

Sultan was a mere puppet of the Bugis Raja Muda and the Dutch in Riau.

Raffles made an agreement with the Temenggong for the establishment of

a factory, but this needed confirmation by the Sultan. Major Farquhar

was sent to try to get this, but as was to be expected, the Raja Muda

and the Sultan were too much in the power of the Dutch to commit

themselves.

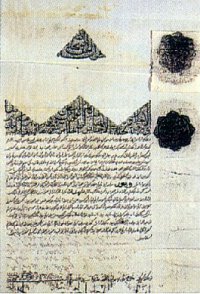

Then

Raffles had another idea. When the late Sultan Mahmud died in 1810 his

eldest son, Tengku Long, was away in Pahang, where he was marrying the

Bendahara's sister. According to Malay custom, the heir to the throne

must take part in the funeral of his predecessor before being

installed. In the absence of Tengku Long, the Bugis Raja Muda had

installed his younger brother, Abdur-Rahman, although there is some

doubt whether this was legally done, because the regalia was still

retained by the wife of the late ruler, who supported the elder

brother's claims. In any case, Tengku Long was living as a penniless

pretender in Riau when two messengers sent by Raffles brought him to

Singapore, where he was received and recognized as the rightful Sultan

Hussein of Johore. A treaty was then made with the new Sultan and the

Temenggong by which they agreed to the East India Company establishing

a factory in return for payments Of $5,ooo a year for the former and

$3,000 for the latter. Then

Raffles had another idea. When the late Sultan Mahmud died in 1810 his

eldest son, Tengku Long, was away in Pahang, where he was marrying the

Bendahara's sister. According to Malay custom, the heir to the throne

must take part in the funeral of his predecessor before being

installed. In the absence of Tengku Long, the Bugis Raja Muda had

installed his younger brother, Abdur-Rahman, although there is some

doubt whether this was legally done, because the regalia was still

retained by the wife of the late ruler, who supported the elder

brother's claims. In any case, Tengku Long was living as a penniless

pretender in Riau when two messengers sent by Raffles brought him to

Singapore, where he was received and recognized as the rightful Sultan

Hussein of Johore. A treaty was then made with the new Sultan and the

Temenggong by which they agreed to the East India Company establishing

a factory in return for payments Of $5,ooo a year for the former and

$3,000 for the latter.

In order to draw to

Singapore all the trade he could, Raffles declared that the port was to

be free and open to the ships of all nations, free of duty, equally and

alike for all. This was the foundation upon which Singapore built up

its great entrepot trade. Raffles hoped to make Singapore a centre of

learning as well as commerce, and laid the foundations of the "

Institution " now named after him. This was originally intended to be

the beginnings of a university where the languages and cultures of the

Malayan peoples could be studied. In order to draw to

Singapore all the trade he could, Raffles declared that the port was to

be free and open to the ships of all nations, free of duty, equally and

alike for all. This was the foundation upon which Singapore built up

its great entrepot trade. Raffles hoped to make Singapore a centre of

learning as well as commerce, and laid the foundations of the "

Institution " now named after him. This was originally intended to be

the beginnings of a university where the languages and cultures of the

Malayan peoples could be studied.

Raffles then returned to

Bencoolen to wind up his affairs there before retiring to Britain. By

this time it was certain that Singapore would not be given up. Raffles

had achieved his object,. but at a terrible personal cost. His first

wife had died in Java, and three of his four children perished in the

unhealthy climate of Bencoolen. He returned to Britain old before his

time and weakened in health if not in spirit. As a crowning misfortune,

the ship in which he sailed was destroyed by fire, and most of the

collection of natural specimens and Malay manuscripts which he had

gathered together was lost. Even after he was in retirement, the East

India Company treated him meanly in money matters and gave him scant

thanks for his great work. In 1826 he died suddenly on the eve of his

forty-sixth birthday. Raffles then returned to

Bencoolen to wind up his affairs there before retiring to Britain. By

this time it was certain that Singapore would not be given up. Raffles

had achieved his object,. but at a terrible personal cost. His first

wife had died in Java, and three of his four children perished in the

unhealthy climate of Bencoolen. He returned to Britain old before his

time and weakened in health if not in spirit. As a crowning misfortune,

the ship in which he sailed was destroyed by fire, and most of the

collection of natural specimens and Malay manuscripts which he had

gathered together was lost. Even after he was in retirement, the East

India Company treated him meanly in money matters and gave him scant

thanks for his great work. In 1826 he died suddenly on the eve of his

forty-sixth birthday.

Write to the author: sabrizain@malaya.org.uk

The

Sejarah Melayu

website is

maintained solely by myself and does not receive any funding

support from any governmental, academic, corporate or other

organizations. If you have found the Sejarah Melayu website useful, any

financial contribution you can make, no matter how small, will be

deeply appreciated and assist greatly in the continued maintenance of

this site.

|

|